March 2 - May 1, 2018

When Richard Royal arrived at the Pilchuck Glass School in the spring of 1978 he was aware that something was going on at the mountain campus that seemed to have sprung from the ground along with the Douglas firs and Norway spruce.

The idyllic retreat founded by Dale Chihuly, Anne Gould Hauberg and John H. Hauberg was no longer a commune of like minded artists celebrating the freedom to create in a pastoral corner of the Hauberg’s tree farm but was slowly and surely blossoming into one of the most important educational institutions of its kind in the world.

When Richard joined the staff of Pilchuck it was ostensibly as a maintenance man. In those early days a guy hired to clean up and a guy hired to drive a truck--Richard and William Morris respectively--might easily find themselves assisting the world’s greatest glass blowers as they worked the hot glass, in demonstrations for students and for themselves after hours and after the summer sessions had ended for the season.

Though Richard was introduced to glass as a student at the Central Washington University he pursued an interest in ceramics and in 1972, he and fellow student Ben Moore built a studio in their hometown of Olympia, Washington. There they created a line of production objects made from clay. The young men worked compulsively and energetically but typically found themselves in bohemian circumstances. Richard made his rent money building high-end wood furniture and endeavored to keep the studio viable while Ben enrolled in the under-graduate program at the California College of Arts.

At CCA, Moore met Dale Chihuly who was running the glass program and who had established himself as a rising young (young rising?) star in the Arts. Chihuly had established the Pilchuck Glass School in Stanwood, Washington in 1971 and he encouraged Ben to come help out during the summer programs. As the small staff of the school expanded to accommodate to explosion of interest in the programming Ben reached out to his buddy Richard, inviting him to join the staff in 1977. Richard jumped at the chance to get out of Olympia where maintaining the ceramics studio had become a lonely enterprise. “I’d heard about what was going on at Pilchuck but I was just thinking about having a job and getting fed regularly. I had no idea what was going to happen…it changed my life.”

After spending the summer of 1978 at Pilchuck, working maintenance and, on many occasions, assisting in the hot-shop during classes and after hours, [DK1] Royal was invited to stay for the fall to assist Chihuly with his work. Chihuly was assembling a large team that he felt would allow him to create ambitious, large scale sculptures and installations. R.M. Campbell in the Seattle Post-Inquirer described Chihuly in an article from that period as, “interested in the experimental, of stretching the technology of glass as far as it can go. Chihuly stresses cooperative efforts… It is Chihuly's belief that with cooperative effort, the field of glass making can be expanded. Pieces can be larger, more complicated. The tradition is European.”

Thomas L. Bosworth, a director of Pilchuck in the 1970’s, wrote that one of the ruling tenets at Pilchuck was an educational emphasis on art as opposed to craft. "They are both aspects in glassblowing, but one can emphasize one or the other. We want(ed) to see what the artists do with the glass.”

Once winter descended on the Pacific Northwest the team was forced to abandon Pilchuck for the season. Chihuly filled his calendar with Visiting Artist Residencies at Colleges and Universities around the country and took members of the team with him. Royal recalls the excitement, “we’d take over the art department and during our demonstrations the hot shop would be standing room only,” the team putting on what amounted to a performance with Chihuly playing the master of ceremonies breathlessly directing the action. “We would hit the campus like rock stars.”

While Chihuly developed a very specific vision of a large studio employing extremely gifted crafts people to handle very specific tasks in an effort to harness the best each had to offer to the process, most artists working in glass in those days worked in very small teams, basically a handful of artist/friends who took turns leading the creation of their own works with the assistance of the others. “We all had our own ideas. In fact, when it was your turn you were expected to have your own ideas for your own work.” And led by the example set by Dale, “everybody was completely supportive of the others and willing to lend a hand if need be.” Dale set the tone, “really supporting whatever each of us wanted to create.”

Royal spent six years working with Chihuly, “searching for my own ideas” before joining Ben Moore at his studio in Seattle in 1984.

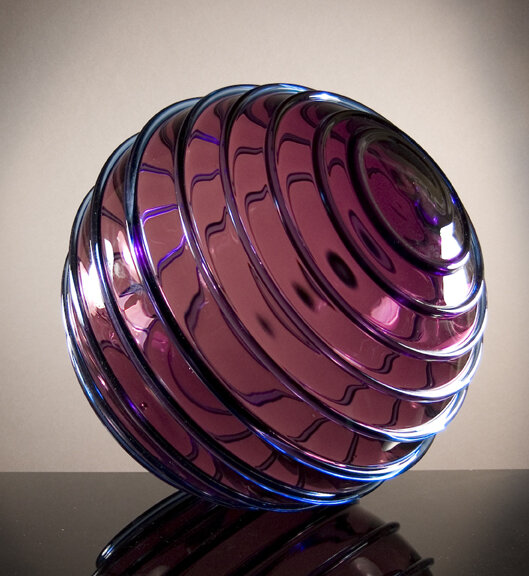

His first series of blown objects to find commercial and critical success, the Diamond Cut and Shelter Series, were begun at this time. In 1995 in an interview with critic and historian Shawn Waggoner for Glass Art Magazine Royal describes his approach. “The Diamond Cut Series was the first I seriously pursued as a series.” The most important technical characteristic of this early work was the overlay of color on the outside of the bubble a strategy that turns the usual process of picking up color first on it’s head. Royal describes the process later in the same interview, “In the Diamond Cut Series I overlaid four or five different colors on the outside of a bubble, brought the blank down to room temperature and used a diamond band saw to cut through those layers…I wanted to create an object that would allow you to look at the outside and inside simultaneously…This was a personal metaphor for exploration, looking inside.” The Shelter Series extended this metaphor reflecting profound changes he was going through emotionally, financially and professionally.

In 1989 his engagement and subsequent marriage to Jana[DK2] led to the Relationship Series. The form, which consists of a top and a bottom of equal size that meet and entwine around a smaller vessel at the center of the sculpture. “The Relationship pieces…show two equal entities coming together around a single idea.” Central to these works was the artist’s sense of scale. Royal committed early on to working in the largest scale that was technically feasible.

Those early bodies of work especially reflect the profound influence Ben Moore and Dale Chihuly had on the artist’s work. Moore’s tight technical approach was itself influenced by Italian Design. Moore blows “on-center” and his work is often characterized by a restrained use of color. Chihuly, on the other hand, had an organic sensibility but his approach to the creative impulse was as much informed by Warhol as by nature. His pieces were gestural, gaudy and loud in color and in form. Royal thinks that his work has benefited from the influence of these two opposites.

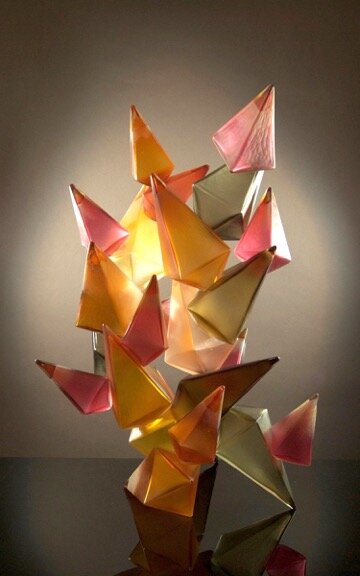

In his latest body of work, the Geos, the artist has sought to capture the qualities of kiln cast glass in his blown glass constructions. He has emphasized simple and subtle coloration and given the individual pieces a sculptural presence by referencing organic forms as opposed to utilitarian objects.

The gallery is especially pleased to mount this history of works by Richard Royal.

Ken Saunders, 2018

Artist | Richard Royal